Read the Full Article: Resolute Racing Shells, The Factory Tour

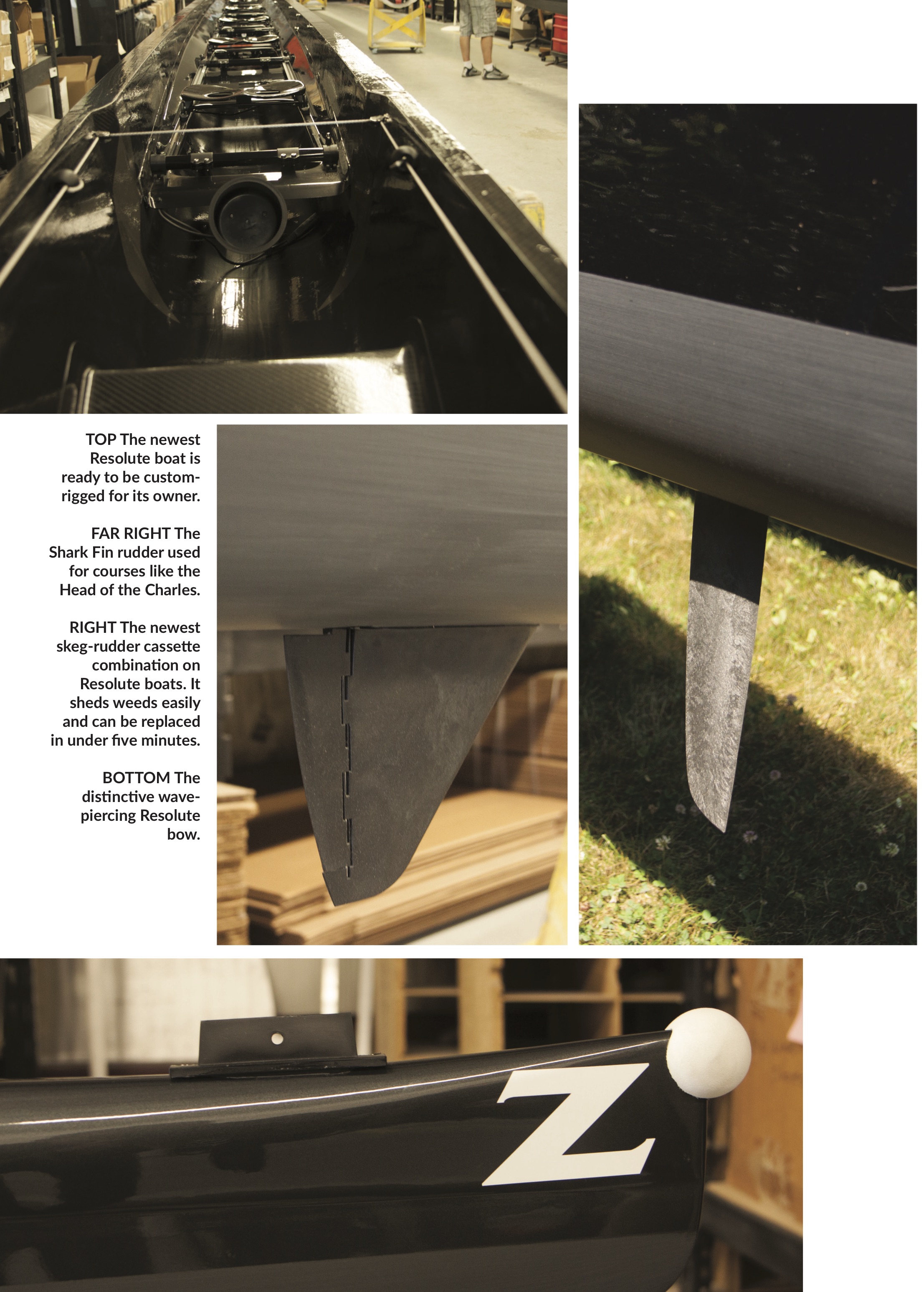

There’s a boat that’s waiting for you. It’s the first boat that Resolute, the boat company started by Steve Gladstone, Eric Goetz and Misha Joukowsky in 1994, ever made. It’s the one they named “Black Z One” because they believed so firmly in the hull shape; they knew it would be the last mold they’d need, the “Z” model. This boat–now twenty years old–is waiting for you to cox it. It’s the boat that still wins gold medals. It’s the boat that can take the Shark Fin skeg-less rudder–a deep wedge of carbon fiber that lets you make shark-like turns on a course like the Head of the Charles–and shave time off your crew’s race. It’s the boat that’s waiting for you.

“Black Z One” greeted me when I stopped in for a tour of the plant where Resolute Racing Shells are made. I was looking for information. I wanted to learn how to gain speed by better understanding the boats we cox. On a summer day in Rhode Island, Jeff Sturges, the president and CEO of Resolute, invited me into the plant to see the “magic” that makes Resolute shells so stiff and responsive. Sturges’ cropped sandy hair, khaki shorts and polo shirt made him look like a boatman at a regatta, but this president and CEO is a rower and an engineer who has decades of experience with composite materials. “Coxswains are a powerful force,” he says, as we settle into a conference room at the front of the plant. “How much do you know about carbon fiber?” Sturges asks. My answer takes us back to the beginning–the basics–of how his team of boat builders uses carbon fiber and honeycomb core to build a rowing shell that started with technology from the America’s Cup racing yachts. “There are really four areas of manufacturing,” he begins, “lamination, assembly, paint and rigging. We want to make sure the crew has a championship row right from the beginning, so we rig every boat to the customer’s specs. It takes a little bit of extra time, but we know our boats are the most expensive out there. We want our customers to have a premium experience.”

Resolute shells are more expensive, but only by 10-15%, Sturges says. The payback for the extra money? “Our very first boat, ‘Black Z One,’ is still winning gold medals. After twenty years, it’s still winning races.” Sturges pauses for a minute and reaches for a cross-section that lets me see inside the guts of a Resolute carbon fiber hull. “The stiffness of a boat is what transmits the rower’s energy to boat speed. We use multiple layers of carbon fiber that add up to a very thin skin on each side of a Nomex Honeycomb to give the hull incredible stiffness, while keeping it light.” I ask Sturges how much his shells weigh. “Every boat is built under it’s allowable [FISA] weight,” he smiles.

Black Z One, the first boat Resolute ever built.

Sturges then goes on to give me a lesson in composite materials that outlines the basics. Of the three most-used composite fibers (fiberglass, kevlar and carbon fiber), carbon fiber is the lightest, has the most stiffness and has very high modulus (resistance to stretching). This means that each shell that comes out of the Resolute factory retains its signature stiffness for decades.

Once Resolute settled on using only carbon fiber in its shells, it chose aerospace-grade unidirectional carbon fiber to run the length of the hull, since unidirectional carbon fiber lays flat and the boat stays stiff over time. In the cockpit and load-bearing areas near the riggers, Resolute uses additional carbon to strengthen particular areas of the boat. In the center of the shell, where the rowers are applying force, a 30 millimeter honeycomb core is combined with the carbon skins on each side to give the hull a toughness and stiffness that can be felt with every stroke. These materials ensure that the rower’s power is transferred to boat speed as efficiently as possible.

The carbon fiber that Resolute uses comes in rolls. It arrives in a refrigerated truck and must be stored in sub-freezing temperatures or else the heat-cured pre-impregnated epoxy resin will begin to activate. Epoxy resin (as opposed to polyester resin or vinyl ester resin) is–again–the most expensive, but it has the strongest physical properties, very little shrinkage when cured, and is excellent at resisting moisture absorption. Each roll of pre-impregnated (“prepreg”) carbon fiber is manufactured with an exact ratio of resin. “Over time,” Sturges explains, “we’ve figured out the optimal resin-to-fiber ratio. Extra resin is just extra weight.”

Using “prepreg” carbon fiber allows the boat builders to work in a clean environment, without the buckets of resin that are used with composites that are not pre-impregnated. Once the carbon fiber is laid into the mold for a particular boat, a vacuum bagging material is applied to the top surface. A vacuum pump is then used when the hull is in the curing oven, to create a vacuum pull during the resin-curing process.

In the factory, even the curing oven is designed to maximize the resin’s properties. Each step of building the hull is “cooked” for at least four hours, with the curing oven first set to maintain temperatures slightly below the cure temperature for a period of time that allows the resins to activate and flow, ensuring the fibers in the hull become tightly compacted under vacuum so there is maximum fiber-to-fiber contact.

Sturges paused for a minute, to let me catch up. “All of this,” he says, as my pen flies across the page of my notebook, “gives us a stronger laminate, a better bond with the honeycomb, and less inter-laminar shear.” When I had first stepped into the factory, I wasn’t thinking about inter-laminar shear, but now, after learning about the materials that comprise a Resolute shell, it all began to make sense. And, it made me remember what coxing a Resolute was like: stiff and loud, but easy to steer. It feels like flying.

“Tell me about coxing your boats. How can we cox them to be faster?” I prompted Sturges for the reason I wanted to understand how Resolutes were made. “You probably need to understand our skegs to really take advantage of our boats,” he said. And with that, he brought out a pile of skegs for us to dig through.

Resolute skegs offer myriad options to coaches and coxswains.

“Resolute’s hydrodynamicists have designed skegs based on their successful America’s Cup yacht racing experience. But you’ll want to know which skeg is best for which course.” Resolute boats carried their original skeg design from 1995 through 2012. The skeg was paired with a rudder that was designed to be used on a straight sprint course. The original skeg attached with a singular bolt, which made it easy to change, but required a bit of time to align and configure the rudder. A new skeg (called a “weed” skeg because it was designed to shed weeds) was introduced in 2012.

There are several rudders that are available for Resolute shells, and this is where the fun begins. The Extended Head Rudder is designed for straight sprint race courses, but its larger surface area is useful when there are crosswinds. The Shark Fin is a rudder that replaces the skeg altogether and allows for extreme maneuverability. Shark Fins are used on head race courses that require tight turns. The skeg box is removed and a Skeg Box Filler is installed, with the Shark Fin acting as both rudder and skeg. The Shark Fin has been used on the Head of the Charles course to give the coxswain the most control over the boat. It is recommended, however, only to use the Shark Fin in an Eight and to practice with it before racing, as it can give a novice coxswain a run for his money!

Another skeg development that’s available is the High Performance Speed Fin, which unifies the skeg and rudder with an elastomer hinge. Two of the most interesting coxing-related features on a Resolute shell, however, are the self-centering steering mechanism and the coxswain hammock. Through a series of pulleys installed on the stern deck, the self-centering steering mechanism returns the rudder to its center position when the coxswain releases her grip on the steering cable. The coxswain hammock is used in a Four and replaces the standard combination of back-support-webbing and headrest-bar with a mesh hammock that the coxswain is suspended in. The best part? The hammock has a padded pillow, minimizing the effect that boat check has on a coxswain’s neck.

Sturges and Sue Hinckley, Resolute’s plant manager, guide me through the myriad bays of their plant; what I find is a team of staff who work their area as if they own their area. There’s a camaraderie that surpasses ego, a natural way of explaining what they’re doing that shows they own their processes. Sturges and Hinckley stand back as the staff detail their work for me; it’s a compelling show of trade know-how combined with pride. Says Hinckley, “We’ve decided not to take shortcuts. It could be done faster, but then we wouldn’t have our hands in it–literally.”

As we come to the end of the factory floor, Sturges shows me a portion of their business that’s emerging as one of the newest things Resolute is proud of: products for disabled athletes. He shows me a wheelchair wheel that uses carbon fiber rims and has shock-absorbing pistons. Hinckley hands me a molded carbon fiber seat that adaptive rowers use in their singles and doubles or on the erg. There’s a pride that surfaces, much like what I had felt when talking with the boat builders on the plant floor.

Resolute is putting their expertise with carbon fiber, resin and curing to use, pushing the development of products for faster rowing by para-rowers. Somehow, it all made sense. The America’s Cup-technology approach Resolute took to create a faster boat is now spilling over into adaptive rowing. The steering features they're building into their skegs, the comfort and safety of their coxswain hammocks, all of this equals a boat company that knows the future is different from the past, and they have the boats to prove it.